Jane Manning James, and the Narratives of Mormon/Religious/American History

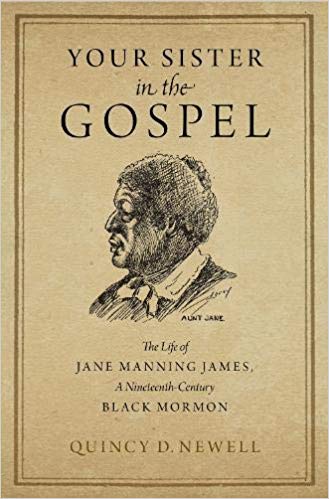

Among the small number of African Americans who converted to the Mormon faith during the nineteenth century, Jane Manning James is perhaps the best known. Born free to a woman who had been born enslaved, Jane’s life exhibited many of the complexities associated with racial discrimination during the era. She joined the LDS church in Connecticut, migrated–mostly by foot–to Nauvoo, lived in Joseph Smith’s home as a housekeeper, and was part of the vanguard company that entered Utah in 1847. She did not die until 1908, which granted her enough time to leave several reminiscences of her unlikely life. By all accounts, her story is a hallmark of dogged faith and preservation.

Among the small number of African Americans who converted to the Mormon faith during the nineteenth century, Jane Manning James is perhaps the best known. Born free to a woman who had been born enslaved, Jane’s life exhibited many of the complexities associated with racial discrimination during the era. She joined the LDS church in Connecticut, migrated–mostly by foot–to Nauvoo, lived in Joseph Smith’s home as a housekeeper, and was part of the vanguard company that entered Utah in 1847. She did not die until 1908, which granted her enough time to leave several reminiscences of her unlikely life. By all accounts, her story is a hallmark of dogged faith and preservation.

Starting a couple decades ago, she began cropping up in many popular places, like the 2005 movie about Joseph Smith that played in LDS visitors centers, often in service of highlighting the founding prophet’s “progressive” racial views, given her insistance that she was treated like family in Nauvoo. And unlike Elijah Able, another early black convert, the fact she was a woman allowed story-tellers to subtly leave out the implications of the priesthood restriction, though her poignant appeals for temple blessings also became a common feature of her contemporary image. In short, Jane Manning James has become part of the modern Mormon psyche, even if she is typically found on the peripheries of traditional narratives, rarely challenging their typical themes and lessons. Read More

In 2016, the LDS Church released, for the first time, the minutes kept in the Council of Fifty. Known as the “kingdom,” the council was created by Joseph Smith in his last few months as a new political order that would return God’s rule to earth. Though the council has been long-known, its minutes have always been deemed confidential and sequestered from researchers. Their publication, then, allowed scholars to reconstruct one of the most audacious moments in Mormon history.

In 2016, the LDS Church released, for the first time, the minutes kept in the Council of Fifty. Known as the “kingdom,” the council was created by Joseph Smith in his last few months as a new political order that would return God’s rule to earth. Though the council has been long-known, its minutes have always been deemed confidential and sequestered from researchers. Their publication, then, allowed scholars to reconstruct one of the most audacious moments in Mormon history. Nauvoo is constantly on my mind. Has been for a while, actually. Before starting The Kingdom of Nauvoo: A Story of Mormon Politics, Plural Marriage, and Power in Nineteenth-Century America—which I’m pleased to share is moving along in the line-editing stage right now, with an early-2020 release date—I was a BYU student participating in their “Semester at Nauvoo” program. For four months I got to live fifty yards from the Nauvoo Temple, where I could learn about the city’s history while walking its streets, touring its homes, and enjoying its gorgeous sunsets. From then on, Nauvoo has always claimed a piece of my soul, which is partly why I jumped at the opportunity to write about it.

Nauvoo is constantly on my mind. Has been for a while, actually. Before starting The Kingdom of Nauvoo: A Story of Mormon Politics, Plural Marriage, and Power in Nineteenth-Century America—which I’m pleased to share is moving along in the line-editing stage right now, with an early-2020 release date—I was a BYU student participating in their “Semester at Nauvoo” program. For four months I got to live fifty yards from the Nauvoo Temple, where I could learn about the city’s history while walking its streets, touring its homes, and enjoying its gorgeous sunsets. From then on, Nauvoo has always claimed a piece of my soul, which is partly why I jumped at the opportunity to write about it.  Yesterday, the Joseph Smith Papers Project released their newest volume:

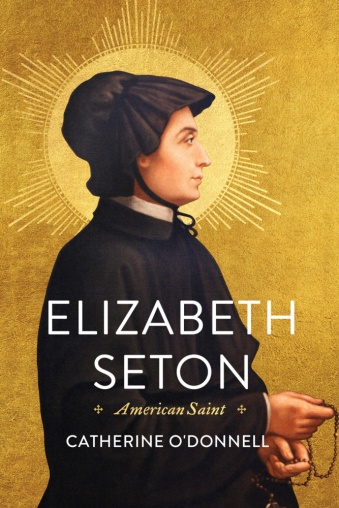

Yesterday, the Joseph Smith Papers Project released their newest volume:  When Elizabeth Bailey Seton arrived back home in New York in 1804, her life was akin to a maelstrom. She was returning from an extended trip to Italy, where she had hoped the temperate climate would heal her ailing husband. It didn’t work. William, her intellectual and spiritual companion, died shortly after their landing in Europe. His economic success had already died a couple years prior: he ran a successful trade with his father, but after his father’s death, William was unable to keep things afloat. So when he himself passed a couple days after Christmas, 1803, in a foreign land, he left his young wife without many prospects. She would have to find a way to scrape by with her five children, all under the age of ten. When she disembarked the ship after the long voyage, and was greeted with the four children she had left behind (only one made the trip to Italy), Elizabeth must have faced a number of difficult emotions.

When Elizabeth Bailey Seton arrived back home in New York in 1804, her life was akin to a maelstrom. She was returning from an extended trip to Italy, where she had hoped the temperate climate would heal her ailing husband. It didn’t work. William, her intellectual and spiritual companion, died shortly after their landing in Europe. His economic success had already died a couple years prior: he ran a successful trade with his father, but after his father’s death, William was unable to keep things afloat. So when he himself passed a couple days after Christmas, 1803, in a foreign land, he left his young wife without many prospects. She would have to find a way to scrape by with her five children, all under the age of ten. When she disembarked the ship after the long voyage, and was greeted with the four children she had left behind (only one made the trip to Italy), Elizabeth must have faced a number of difficult emotions.