Reflections on the Recent Issue of Journal of Mormon History

I finally go around to reading the most recent issue of Journal of Mormon History. As always, there was a lot to chew on. Here are just a few highlights.

- I really liked Matthew Dougherty’s sophisticated and provocative article, “None Can Deliver: Imagining Lamanites and Feeling Mormon, 1837-1847.” This essay added a new lens to an important topic, how Mormons conceived of Native Americans, in an impressively theoretical way: the study of emotions and feelings. How did the image of Indians validate Mormon beliefs concerning chosenness and millennial justice? Lots of scholarship has pointed to Mormon alliances with indigenous tribes, something that seemingly makes them unique, but Dougherty convincingly highlights how Mormons appropriated common racial beliefs in doing so. (Including support for forced Indian removal.) And in looking toward the Amerindian apocalypse, Mormons were anxious to cast off the feeling of violent justice off their own shoulders. “Early stories about Lamanites, then,” the article explains, “did not exalt American Indians above white Mormons but rather suppressed or downplayed Native people’s actual needs in favor of imagining a holy people who could enact Mormon prophesies” (44). Mormon conceptions of interracial unions were complex.

- I also enjoyed Matthew Godfrey’s “Wise Men and Wise Women: The Church Members in Financing Church Operations, 1834-1835,” which is a straight-forward account of fundraising efforts in Kirtland. It turns out that churches need money to survive, especially if they have grand expectations for audacious projects. As such, the young LDS faith was in constant need for cash. Lacking the business endeavors of the later Utah period, not to mention a standardized system of tithing, they turned to donations. This is where average members came in. I especially appreciated the attention to women, many of whom we know too little about. This is another example of how the large designs of church leaders would not have existed if not for popular support.

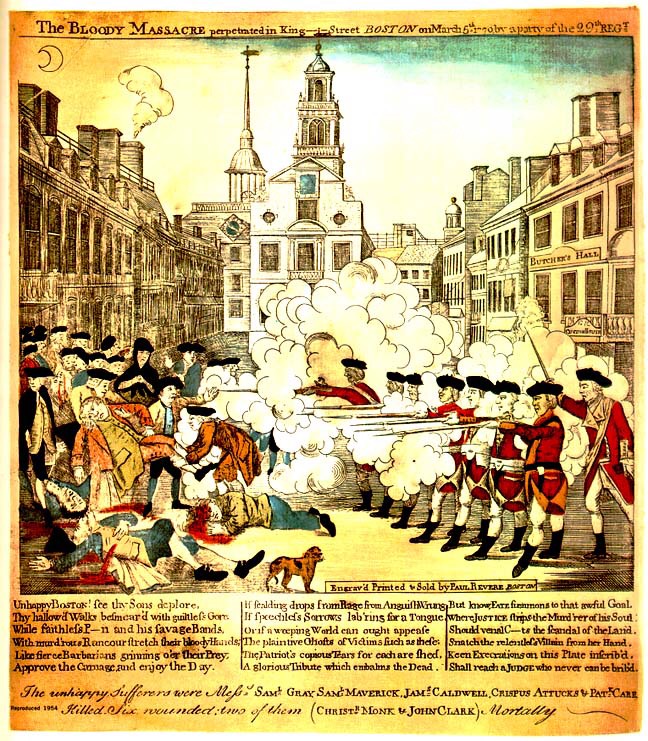

- Some of the best work JMH publishes is outside the narrow boundaries of history. James Swensen’s “Reflections in the Water: An Exploration of the Various Ises of C. R. Savage’s 1875 Photograph of the Mass Baptism of the Shivwit” is a great example. Swensen, who teaches art history, traces the reception history of a famous picture. (It’s the image featured in this post.) Taken when over a hundred members of a local tribe entered the Mormon fold, the image had a long shelf life. To Mormons during the 1870s, it represented a fulfilled promise that the Lamanites would accept the gospel; to gentile observers, it was proof of the Native/Mormon alliance. Later, scholars used it as evidence of cultural imperialism; conversely, others argued it depicted Native People exercising agency and making diplomatic alliances.

- The other articles are also excellent. Two of them, by Alisha Erin Hillam and Darcee Barnes, were written by independent historians, and represent the broad tent JMH does (and should) create.

- There is an exceptionally long book review section, which I understand is due to an error. (The reviews from the previous issue weren’t printed, so they were doubled up in this one.) As always, the quality of these reviews can be uneven, but there are plenty of good ones. My favorites were those written by grade students who display an exciting grasp of new historiographies. This includes not one but two reviews by Cristina Rosetti, a PhD candidate at UC-Riverside, as well Joseph Stuart, a PhD candidate at Utah. But also check out Matt Bowman’s thoughtful take on Tom Simpson’s award winning American Universities and the Rise of Modern Mormonism.

- I especially enjoyed the exhibit review by Richard Bushman, where he reacts to the year-old remodel of the LDS Church History Museum. The prose is quite flowery (the museum could use portions of it for marketing brochures!), but he also raises incisive critiques. (Besides that, as an octogenarian, he missed the old escalators and had to anxiously look for the elevators.) Bushman notes that the museum has a bit of difficulty handling the Book of Mormon. How should one square this ancient record with a modern story? They chose to merely tell it within the context of Joseph Smith’s own life, rather than dwell on its historicity claims. Second, the exhibit demonstrates some transparency (seer stones and polygamy) but in limited ways (doesn’t depict Smith using the stones, and no mention of Smith’s own polygamous practice). And finally, Bushman explains that the new exhibit both condenses and expands the story: condenses, because it cuts the tale off at Nauvoo; expands, because it focuses on he broad concept of visions. “The parochial story of Utah and the gathering gives way to the universal story of a new revelation” (147). I appreciate this take, but I do note the irony that, in a day when the Church History Department is more focused on global stories, the entire first floor of its museum is dedicated to twenty years of an American tale.

Anyways, it’s a solid issue. Happy reading!